(Genesis Chapter 1)

On March 5, 1681, the English King Charles II granted a Charter of land to the Quaker Gentleman, William Penn. This Charter was for land located across the Atlantic Ocean eventually known as “Penn’s Woods” or Pennsylvania. From its founding as an English colony in 1681 until the beginning of the French and Indian War in 1754, the relationship between the local Delaware, or Lenape, Indians and the English settlers seems to have been relatively friendly here in what William Penn envisioned as his “Peaceable Kingdom.” However, what, in the first place, gave a foreign king from across the wide ocean the right to grant to one of his subjects land here in the North American continent, already inhabited by others… is an important question of Native American justice that rarely if ever gets raised in the early histories. This question has again come front and center in present day American politics regarding immigration policy. From the perspective of the Native Americans, our early English forebears were themselves illegal immigrants.

William Penn would not set foot in the New World for the first time until a year and a half later on October 28 or 29, 1682. Penn’s Landing was in the only town in the Province at the time, then known as Upland and located along the Delaware River. It had been founded thirty-eight years earlier in 1644 by the Swedes, who were the first European settlers in the area. Today, Upland is one of the neighborhoods of Chester, the oldest city in the State of Pennsylvania, predating Philadelphia which was founded by Penn in 1682.

The English Provence of Pennsylvania was originally chartered as a Quaker colony, but it also offered “a haven to all Creeds on a broad basis of religious freedom.” (Hannum, p. 7) Religious freedom was a rather radical idea in that age of established State Religions. The Quakers sought asylum here in America because they were being persecuted by the Puritan and Anglican establishments back in England. The establishment of the Anglican Church in Pennsylvania was ensured by a stipulation in the original Land Charter to William Penn that stated that any twenty inhabitants of the colony could make a request to the Bishop of London for their own church and priest. It is ironic, then, that the persecuted Quakers had to ensure the establishment of the church of their persecutors, the Presbyterians and Anglicans.

The thirteen American colonies were under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of London at the time. Because there were no bishops in the American colonies, if an English colonist wanted to be ordained in the Church of England, he had to make the long trip via wooden, sailing ship across the Atlantic ocean to London. There he (Women would not yet be ordained in the Anglican/Episcopal Church until the 1970s.) would be examined and ordained by the Bishop of London in St. Paul’s Cathedral, and then make the long and perilous trip back to the colonies. They must have been dedicated individuals and men of some wealth and means to afford the education and travel.

“Some seed…fell into good soil.”

(Matthew 13:8)

One of those dedicated individuals was a Scotsman named George Keith. Keith was born in Aberdeenshire, Scotland in 1638/9 to a Presbyterian family. He received an M.A. from the University of Aberdeen. He joined the Religious Society of Friends in the 1660s and was acquainted with George Fox, the founder of the Quakers and William Penn. Around 1691 Keith decided that the Quakers had strayed too far from orthodox Christianity and began to have sharp disagreements with his fellow Quakers regarding the doctrine of the Trinity and the Gospel sacraments of baptism and communion. He broke from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting and formed a group known as the Christian Quakers or Keithian Quakers. In 1693 he and his fellow Keithians published one of the earliest printed anti-slavery tracts published in British North America, entitled “An Exhortation & Caution to Friends Concerning the Buying or Keeping of Negros.”

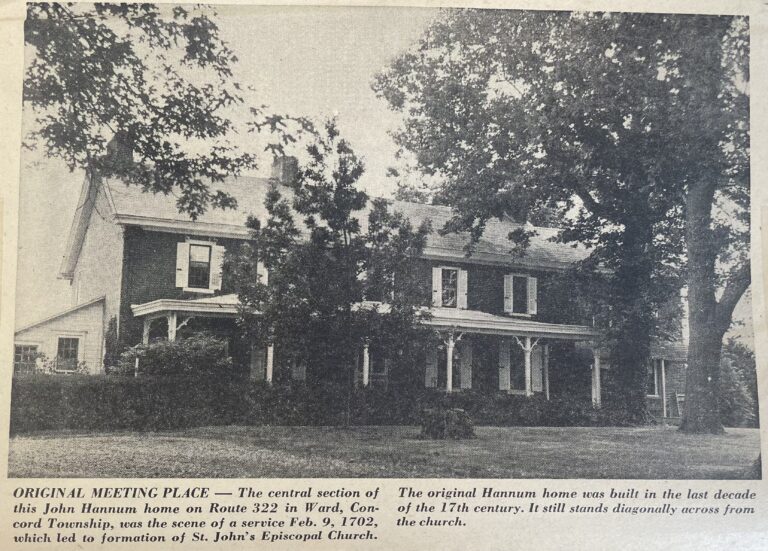

Keith would persuade several other Quakers in Chester County, which then also encompassed Delaware County, to join him and they were all baptized in Ridley Creek in the 1690s. Among those baptized were John Hannum and his wife Margery Southery of Concord. John and Margery were two of the founding members of St. John’s Episcopal Church.

Keith returned to England where he was disowned by the London Yearly Meeting of the Quakers in 1694. In 1699 he critiqued William Penn and other Quakers as being Deists. There was some validity to his charge. For example: two famous Quakers and early American patriots, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine, would later claim to be Deists.

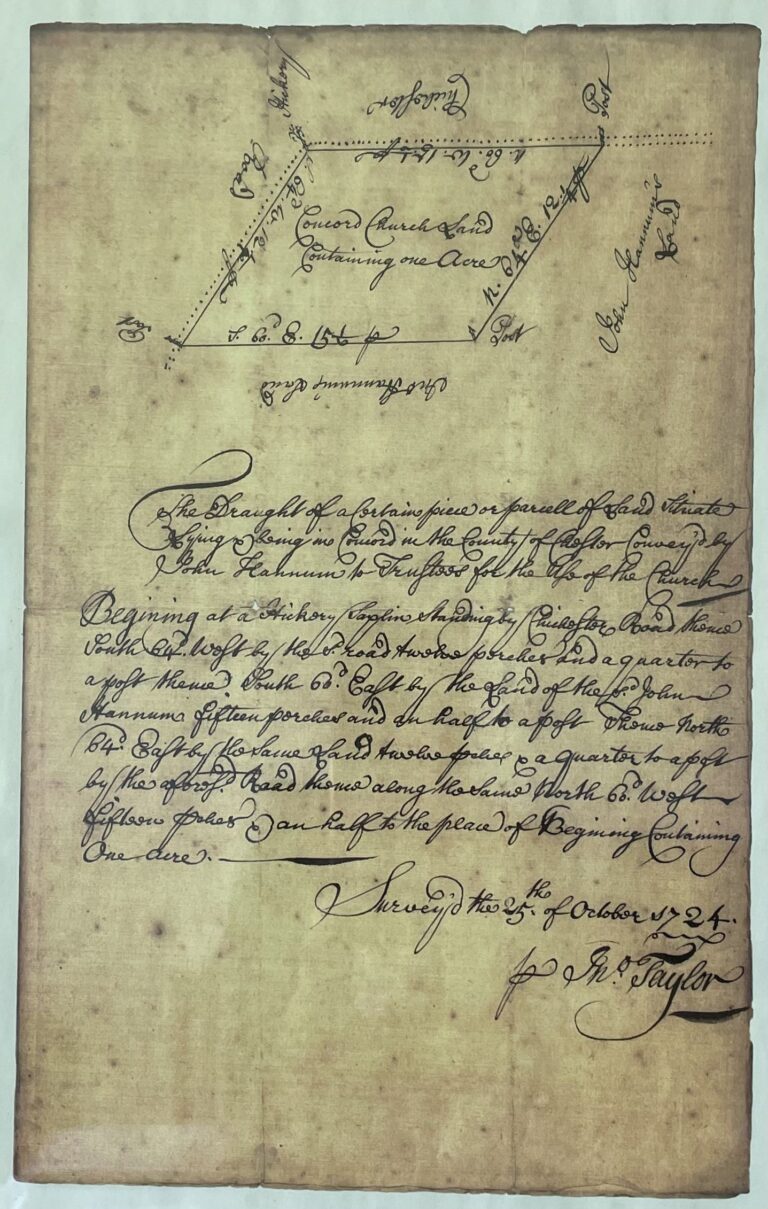

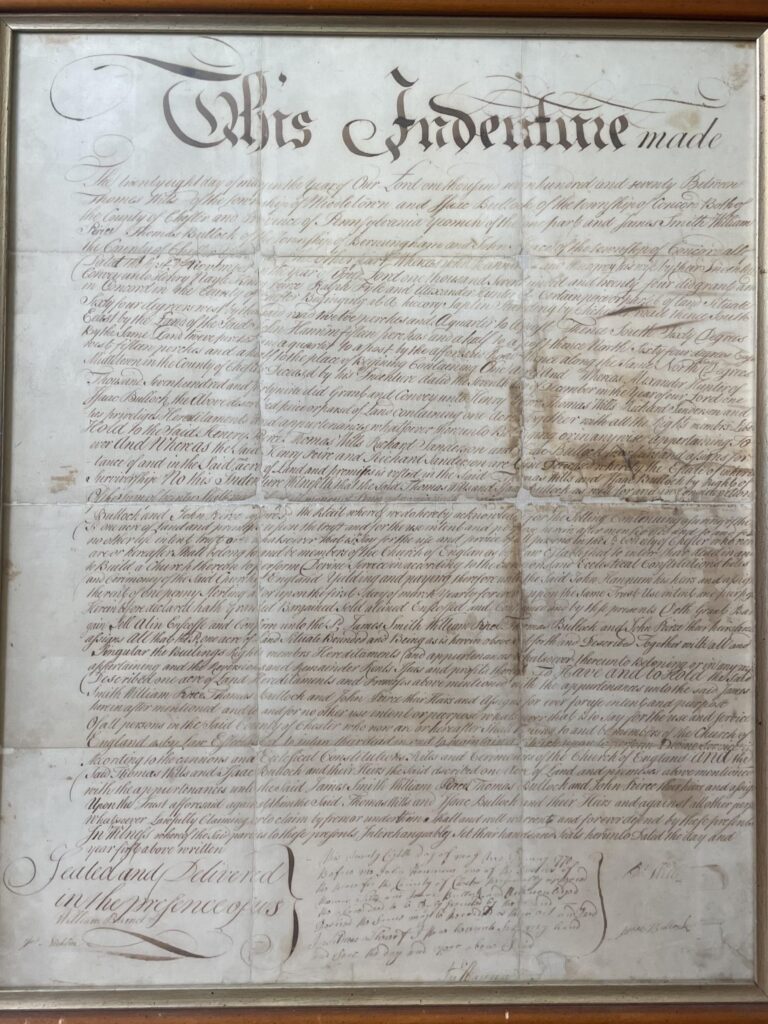

In 1700 George Keith was ordained an Anglican priest in the Church of England. He was sponsored by a Missionary Society of the Church of England, the “Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts” and returned to Pennsylvania as a missionary priest from 1702 -1704. In December 1702, he conducted worship services in the Hannum home and on subsequent Sundays in the homes of other Keithian Quakers who also had joined the Church of England. The Hannums eventually gave the acre of ground on which the first church building, a log structure, was built and a churchyard for burials was created. The north west corner of the site of the original log church is marked by a marker in the old churchyard across the driveway down north of the present church building. The church may have been named after John Hannum. The original Hannum house still stands and is located just up Concord Pike southeast and across from the church.

So, St. John’s Church along with St. Paul’s in Chester and now defunct St. Martin’s Church in Marcus Hook were three ‘Society for the Propagation of the Gospel’ churches established in the colonies in 1702.

Worship and Music

The Rev. George Keith would have used the 1662 version of the Book of Common Prayer and the 1611 King James Version of the Bible. Anglicans sang metrical versions of the psalms in those days (For example: see Hymns # 380 & 680 in the 1982 Episcopal Hymnal) rather than hymns, which did not come into wide spread use until the second half of the eighteenth century. There are old copies of the 1662 Prayer Book published in the 1700s in the church archives, along with a King James Bible published in 1703 and several other old Bibles.

Slavery during the Colonial Period

Slavery has been called the “original sin” of America. There were many more African slaves in the south, but slavery was a part of life throughout the Thirteen Colonies, including Pennsylvania. Records show that there were many slaves in Chester county (which included Delaware county at that time), but perhaps no more than one or two per owner. The sad fact is that several of the original members of St. John’s Church and many of its early priests were slave owners.

Because of the anti-slavery work of the Quakers and others, slavery did gradually die out in Chester county towards the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th Centuries.

“God gave the increase.”

(1st Corinthians 3:6)

It is fairly well established that St. John’s first church building, a rectangular log structure, was erected in 1702. It was located in the middle of the churchyard just north of the Fawcett lot. The dimensions are said to have been 24 x 36 feet. Church records for the first 25 years through 1727 were lost due to an “ill accident.” (Hannum, p. 13)

Church Exterior

So, beyond the brief description in the previous paragraph of shape, size, and location, we have no account of what it may have looked like inside or out. There is an old drawing of St. Paul’s first church building in Chester that gives an idea of what St. John’s first log church may have looked like. A guess would be that it was made of logs, chinked with mud or cement, and white washed inside as well as out. It may have been two stories with angled roof, and was probably oriented east – west with a door in the long, south side and several windows throughout. A faint impression of the original foundation can still be detected in the ground where it was probably located. There may have been long rows of covered sheds for horse and buggies, hitching posts for others, outdoor privies, and perhaps a well for water. The local Anglicans worshiped in this first church structure for eighty-eight years.

In 1773, just before the American Revolution, a brick addition was added to the west end of the old log church. Bricks were used as ship’s ballast and replaced with other trade goods. Records show that 20,000 bricks were purchased for 1 pd. 10s. per thousand, a rather expensive item for the day. Lime, nails and boards were also purchased along with “5 quarts of rum at raising of ye rafters” and “2 quarts of rum to ye carpenters.” (Hannum, p. 18) Rum was an important commodity in the very lucrative British Mercantile system of the day. Those early Episcopalians knew how to “raise the roof” even back then.

In 1790, “an eastern end, laid with stone, replaced the early rude structure…thus completing the transformation of the small log church into a commodious edifice of stone and brick, sometimes called the Second Church.” (Hannum, p. 18-19)

The Interior of a Typical Colonial Anglican Church

We can speculate that the interiors of the 1st log church of 1702 and the 2nd stone and brick church of 1790, being a country church, were probably rather plain. The interior was probably white washed throughout with bare rafter ceilings. There may have been a wraparound balcony on three walls for poorer families, servants and family slaves. A double-decker pulpit-lectern was probably centered against the east wall with a small altar-table under the lectern and stairs climbing up to the pulpit area. Sometimes the pulpit-lectern in colonial Episcopal churches was centered on a side wall with the altar-table centered separately on an end wall and even in a separate space attached to the church. Many churches had seating facing one another with isle down the length of the church. The pulpit lectern was at one end and the altar-table at the other.

The Lord’s Prayer, the Apostles’ Creed, and the Ten Commandments were often prominently displayed on the wall on either side of the altar-table in colonial Anglican churches. This is the case in the parish church of a British friend of mine, St. Gile’s Anglican Church, which dates back to the 11th Century. Finally, there would also have been a Baptismal Font or silver basin for baptisms.

An altar rail may have been placed around the altar table. At first, church members probably did not kneel at the altar rail to receive Holy Communion. Rather, the purpose of altar rails was to protect the altar-table with its precious linens and hangings from the occasional stray, male dog. Churches were often kept open in those days, back in England as well as in the colonies, so altar rail slats had to be wide and close together to keep the animals at a safe distance.

On the altar table would have been a “fair white linen” or “clean white cloth,” the only accoutrement ever required by any Prayer Book. The Queen Anne Communion Set, brought to the congregation from Queen herself by the Rev. Evan Evans sometime in 1707/8, would have been displayed on the altar with a loaf of real bread and plenty of good, red wine in the carafe. All would be covered with a white linen cloth. There probably were flowers or other bits of nature appropriate to the season decorating the church as well. Often churches would have a festive set of altar coverings for high Holy Days, and a plainer set or no hangings at all for Lent and other times during the church year. Liturgical colors did not come into common use in the Episcopal Church until the Catholic Revival of the 19th Century.

A large 1611 Authorized King James Version of the Bible would have been displayed on the lectern below the pulpit for anyone to read from at any time, and plenty of Prayer Books would have been available throughout the church. Metrical Psalm books containing a few additional metrical hymns may have also been available in the early 18th Century.

Only large city churches had organs. Pianos were not yet available. Most singing in local country churches was done acapella and perhaps accompanied by local fiddlers and/or other musicians. There may have been a small choir that sang anthems during the Offertory and while people received Holy Communion. Not everyone was literate in the early 1700s, so, if not already memorized, many prayers and much of the singing would have been lined out by the clerk (who was a kind of combined Lay Reader and Music Director) and repeated by the congregation.

There were no candles or crosses or vases on the altar-table. These were considered to be too popish. Candles for lighting may have been on either side of the pulpit and the lectern. Wealthier churches may have had hanging chandeliers and candle sconces on the walls. There were no stained-glass windows, so church members enjoyed plenty of light through the clear glass windows and with the white-washed walls. Worshipers would also be inspired by their easy view of the surrounding countryside and the changing seasonal beauties of God’s very good creation, a very Celtic thing.

Poorer church members, servants and slaves probably sat on rough-hewn benches in the balcony. If there were pews on the main floor, they would have been completely boxed in because churches were not heated and rather drafty in the winter. Families had their own pews which they entered by a hinged door. Folks wore plenty of clothes and brought blankets and hot bricks from home to keep warm in the winter months. Churches were supported by annual pew taxes payed by parishioners.

Anglican priests were often the only educated person in a local village or town, hence they were addressed as Parson and formally referred to as “the Reverend, Mister/Doctor” so and so. Priests’ vestments were black cassocks covered by a long, white Anglican surplice that went down to the ankles and had long, puffy sleeves, a black tippet instead of a stole, and preaching tabs at the neck. They may have worn pectoral crosses or other religious jewelry. Colored vestments and many other practices, such as processionals and recessionals and candles and crosses on altars usually seen throughout the Episcopal Church today, would not come into common use until the Catholic Revival of the 19th Century.

Sunday Church Worship and Music in Colonial Days

Going to church was the main form of socializing in early colonial times. People came prepared to spend the whole day at church bringing food and drink as well as enough hot bricks (or perhaps hot potatoes) and blankets in winter for the whole family. On the Sundays when Holy Communion was celebrated, which was at least once a quarter and as often as once a month, worship began with Daily Morning Prayer in which you would say several psalms, listen to Bible lessons from the Old and New Testaments as well as a Gospel lesson. The Parson would then preach a learned sermon that lasted for at least an hour.

Those who were going to receive Holy Communion would then leave their pews when the priest called them to confess their sins with the words “Draw near with faith, and make your humble confession to Almighty God, devoutly kneeling.” (BCP, p. 330) They would kneel on the floor around the altar-table, remaining on their knees throughout the General Confession and Absolution, the Prayer of Consecration, and to receive the Bread and Wine of the sacrament, returning to their pews for the Postcommunion Prayer and end of worship. The priest celebrated communion not with his back to the people but standing at the side of the altar where all of his actions could be clearly seen by the people.

Worship may have taken two to three hours. There was then a break for lunch (those hot potatoes were then eaten) and plenty of socializing. There were no Sunday Schools in those times, but there may have been Catechetical instruction and meetings for other business. The church space was used not just for worship. Sunday church ended in the late afternoon with Daily Evening Prayer, then all went home on horse back, in buggies, or via shanks mare. Episcopalians were hardy church goers in those days. Just think how we now complain when worship goes over an hour or sermons are longer than twelve minutes.

St. Paul’s in Chester, St. Martin’s in Marcus Hook and St. John’s in Concord shared a minister and pastoral services were irregular during the early years. On occasion Swedish Lutheran pastors from the church in Christiana (Wilmington, DE) generously offered their pastoral services.

The Diary reminiscences of a John H. Brinton are in the files of the Chester County Historical Society in West Chester, PA. He says in his diary that he was acquainted with an old man who had worshiped in St. John’s early log church. This man told of the men of the congregation keeping guard, with their guns, outside the church to keep the Indians from disturbing worship. The local Lenape Indians did not seem that hostile to the early settlers. The Quakers had an excellent relationship with them. Perhaps armed church guards were needed during the French and Indian War of 1756 – 1763 when the Indian allies of the French were a real threat to the English settlers throughout much of Pennsylvania. Sadly, today, many churches are employing armed guards and holding preparedness drills to protect themselves from the mass shootings that have been happening in churches and other public venues. This is a disturbing commentary on our times.

Including the Rev. George Keith, ten priests served the people of St. John’s Church during this early log church period from 1702 – 1790. All of the dedicated and devout clergy who have served St. John’s Episcopal Church, Concord from its founding to the present day are listed at the end of this brief history.

“Times That Tried Men’s Souls”

Two priests in particular served during the years of the American Revolution 1775 – 1783: the Rev. George Craig 1759 – 1779; and the Rev. John Wade 1780 – 1787. These were “times that tried men’s souls,” as Thomas Paine wrote in his famous “Common Sense.”

Because of the Act of Uniformity passed during the reign of King Charles II 1660 – 1685, as part of their ordination vows, all priest of the Church of England swore allegiance to the King of England. This put the Revs. Craig and Wade in a very difficult position during the years of the Revolutionary War. Many clergy and other loyalists fled to Canada. If they stayed with their charges, they were often branded as Tories. One Anglican priest in Maryland was known to have had two loaded flintlock pistols with him on either side of the pulpit when he preached.

There is no indication of the political sympathies of either Rev. Craig or Rev. Wade. They probably regarded their pastoral loyalty to their flock, patriot and loyalist alike, as transcending any personal political loyalties they may have had. The Rev. Mr. Craig may have buried in St. John’s churchyard the dead of both sides who had fallen during the Battle of Brandywine Creek on September 11, 1777. This was the largest land battle of the American Revolution and took place at Chadds Ford, just six miles south on Baltimore Pike (Rt. 1). Many area churches and meeting houses were used as hospitals for the wounded from this battle. This may have been the case for St. John’s Church since it was so close to the battle, but there is no record of it.

On page 38 of his history of the church, Hannum states that bits of British uniforms and buttons had been found in the north east corner of the church yard, “proving the interment of British soldiers, who were slain in the Battle of Brandywine.” If there were such archeological evidence, it is now lost. According to an old family tradition, the remains of an American soldier at the Battle of Brandywine, named William Weston, are buried in the northwest corner of the churchyard as well. He was said to have carried the first “Stars and Stripes” in the battle. There is no evidence for this either.

A New Episcopal Church and Book of Common Prayer

It is a small miracle that the Episcopal Church even survived the American Revolution. The church was very closely identified with the British enemy. Most importantly, there were no bishops here in the colonies to ordained new deacons, priests or bishops for the fledgling church. So, the first order of business was to get bishops for the new church. A new Prayer Book also had to be published.

In 1784 Samuel Seabury from Connecticut was ordained as the 1st Bishop of the American Episcopal Church. He was ordained in Scotland by descendants of the Non-Juring bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church. The Scottish Bishops prevailed upon Bishop Seabury to have their Scottish Episcopal prayers made part of the first American Book of Common Prayer which was published five years later in 1789. As a result, our first Episcopal Prayer Book is very Scottish. For instance: the Eucharistic Prayer is from the Scottish Prayer Book and theologically more catholic than the English book of 1662. This Scottish Eucharistic Prayer was included in all of the American Prayer Books (1789, 1892, 1928, 1979) and is part of Rite I in the 1979 book presently in use. It also influences Eucharistic Prayer A of Rite II.

At first the English Bishops refused to ordain the Americans, which is why Seabury went to Scotland to be ordained. But they eventually agreed to ordain bishops for the Americans and in 1787 William White of Philadelphia and Samuel Provoost of New York were ordained in St. Paul’s Cathedral by the Bishop of London and other English Bishops. Bishop White would become the first Presiding Bishop of the young American church. The new American Episcopal Church finally had three bishops, the required number to ordain future bishops, priests and deacons for the American church.

The Rev. James Conner became the Rector of St. John’s Church in 1788. On March 26 of that year, the Vestry addressed a letter to Bishop White in Philadelphia: “Resolved unanimously that ye thanks of this congregation be returned to ye Right Rev. Dr. White for his kind attention in sending to us ye Revd. James Conner, who has given us general satisfaction.” The Rev. Conner may have been ordained deacon and then priest by Bishop White.

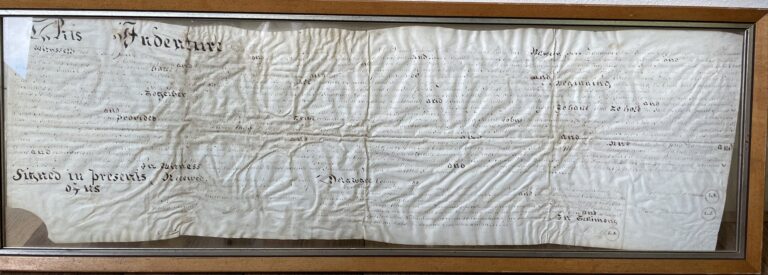

The original Charter of Incorporation of St. John’s Church is dated June 30, 1818. In 1833 a twenty-foot stone extension was added to the west end of the 1790 church perhaps replacing the brick portion, and the pulpit was moved to the west end of the church. The priest at the time, the Rev. John B. Clemson, added this note to the minutes of May 20, 1834: “The Church at this time is in greater prosperity than has been for many years before.” Worship services from that date on were held twice a month. The National Episcopal Church was also beginning to thrive and quickly spread west to the new states of the young country.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

In order to improve attendance at vestry meetings, apparently a problem even back then, a drastic new rule was adopted in 1836. Beginning on Easter Monday of 1837, Vestry Meetings would be held once a quarter and vestry members would be fined 25 cents for every meeting missed, except in the case of sickness. It seems a mysterious illness swept through the parish that year, to which vestry members were peculiarly susceptible. No Vestry Meetings were held for that whole year.

The Church on the Hill

“Build thee more stately mansions, O my soul! Leave thy low-vaulted past!”

(Oliver Wendell Holmes)

The first mention of a “church on the hill” is in the Minutes of August 2, 1843. “Resolved that the church be repaired in its present form, (negatived). It was then resolved that the building be removed, and a new church erected on the hill, provided sufficient funds are raised for that purpose (carried).”

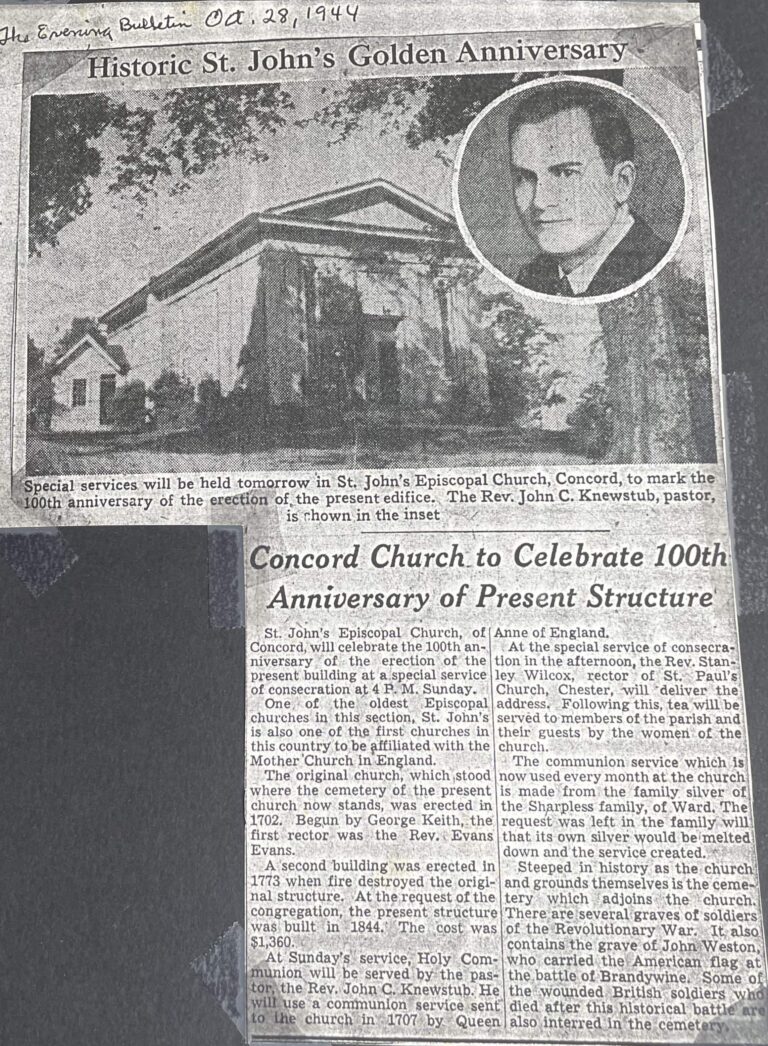

Eight months later, in April of 1844, arrangements were made with Joseph Hannum for the purchase of additional land for the new church. Joseph was the descendent of John who gave the land for the original church in 1702. In May the Vestry contracted with Peter Smith to build the present building for $1,360. Materials from the old church building were used in the building of the new. The general plan and finish of St. James’ Episcopal Church in Downingtown, PA was used for the new church. The cornerstone was laid June 15, 1844 and construction completed by October of the same year.

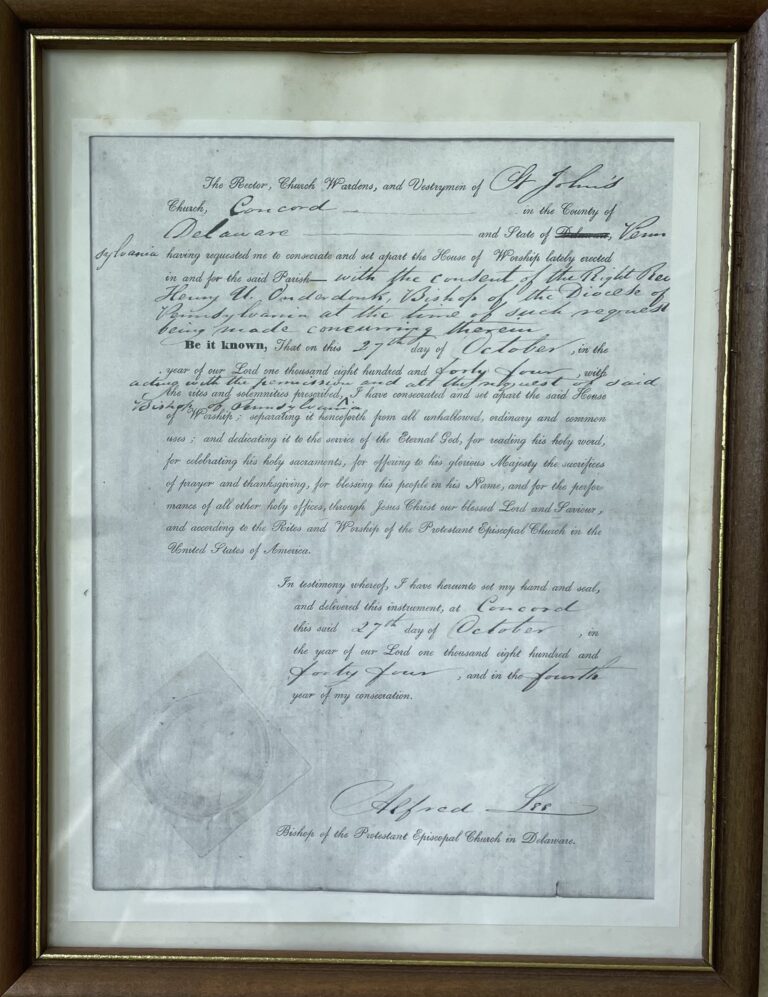

By arrangement with Bishop Onderdonk, then Bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, the Rt. Rev. Alfred Lee, recently consecrated Bishop of Delaware consecrated the new church on October 27, 1844. Five years previous, Bishop Lee had supplied at St. John’s Church and so endeared himself to the congregation that they recognized his self-sacrificing devotion in a resolution of appreciation and invited him to consecrate their new church building.

Church Exterior

The exterior of the church probably looked very similar to what it looks like now. The sacristy, called the vestry then or robing room, was “small, cramped, cold, damp, generally uncomfortable, and had a leaky roof.” This may account for why the vestry preferred to meet in parishioners’ homes for their meetings. A stove was added for heat. The present vestry/sacristy was completed in 1901.

Church Interior

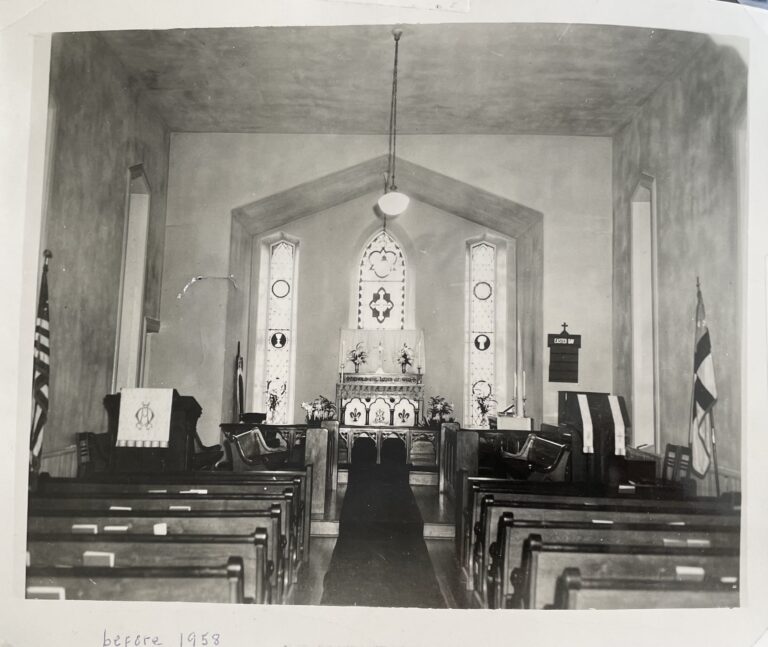

The interior of the new church building looked somewhat different than it does today. The choir sat in the balcony, which was the typical location for choirs in early Anglican/Episcopal Churches, and an excellent location for supporting the worship of the congregation. In 1854 seating was provided in the balcony. It is unclear what the choir sat on before this.

Hannum states that the pulpit was in the center of the chancel. But this is somewhat misleading. At first the pulpit was probably still a combined pulpit/lectern and centered on the front wall, which had no window at that time. A small altar/table stood below the pulpit lectern. The pews were of the old boxed pew enclosed type. People bundled up and brought their hot rocks or bricks or hot potatoes with them to keep warm. The boxed pews protected them from cold breezes. A heater was finally put in the church in 1854. It is unclear whether this referred to the stove in the sacristy or was an early form of central heating, probably coal fired. In 1887 the enclosed pews were removed and replaced with plain bench pews, which may indicat that there was central heating by this time. These pews were used for more than seventy years. Some are still used in the gallery. Electricity may not have come to the Glen Mills area or the church and rectory until as late as the 1920s or 1930s.

The first mention of an insurance policy on St. John’s Church was in 1852. The vestry purchased a policy for $1,000 from the Mutual Insurance Office of Chester County.

In 1870 the stained-glass window dedicated to Bishop Onderdonk was installed along with windows to either side. These side windows are now located on the right and left sides at the front of the main church. The window in the center of the south east side of the church (the organ console side) bears the inscription “Irene.” It was a memorial to Irene Paschall, who was born when peace terms were signed at the end of the tragic and devastating American Civil War. “Irene” means “Peace.”

Worship and Music

In 1854 a melodeon was purchased. This was a small reed organ. The air was supplied by foot peddles pumped by the organist. This is the first mention of a keyboard instrument used for worship. It was located in the balcony.

In 1866 the melodeon was replaced by a more suitable instrument, which may have been a small tracker reed organ with an air supply provided by pumps activated by another person other than the organist. This instrument remained in the gallery until 1881, when it was moved to the front of the church. William E. Hannum, author of “The Story of St. John’s,” remembers pumping the organ as a young boy. He thought it an instrument of torture. A third organ was purchased in 1898 for $225. It was probably another tracker organ with an air supply coming from a separate pumper. In 1951 an electric Hammond organ was purchased. The present organ is about thirty-six years old.

The first Episcopal Book of Common Prayer published in 1789 would have been in use in St. John’s Church. Worship and accoutrements were probably very similar to colonial times. In 1874 a cross, candlesticks, and vases made their appearance in the church. But, after a spirited discussion, the vestry voted to remove them from the church.

Since the First Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s and the rise of Methodism and the Evangelical movements, there would have been more hymn singing and less singing of metrical psalms. By the time of the 2nd Great Awakening, which began in the 1790s and reached its peak in the late 1840s, American religion was characterized by enthusiasm, emotionalism and Methodist hymn singing. Episcopal Churches were slow to adopt these innovations and were generally more reserved in emotional expression. This is characteristic of most Episcopal worship to this day.

The Prayer Book was revised for the first time in 1892. By this time, Methodist style hymnody had been adopted throughout most of the Episcopal Church and several Hymnals had been published during the 19th Century.

The Temperance Movement went hand in hand with the 2nd Great Awakening. Taking the oath to foreswear the use of alcohol was considered an important part of an awakening of faith. Alcohol use was a problem in early America. One abuse was to give it to children to ease their suffering in the days before child labor laws. Many Episcopalians did take the oath, but most lived by the philosophy of “all things in moderation” regarding the use alcoholic beverages.

The Horse Sheds

Horse Sheds were universal in the early days before the automobile. Hannum says that Horse Sheds first appeared at St. John’s in 1853, but they may have present in colonial days as well. The 1853 sheds were located along Chester Road (Concord Road), facing away from the road. They were removed to the southwest side of the church at a later date. Owners were required to build, maintain and move the sheds at their own expense. The Vestry did provide hitching posts for those who could not afford their own sheds. These Horse Sheds were finally taken down in 1928.

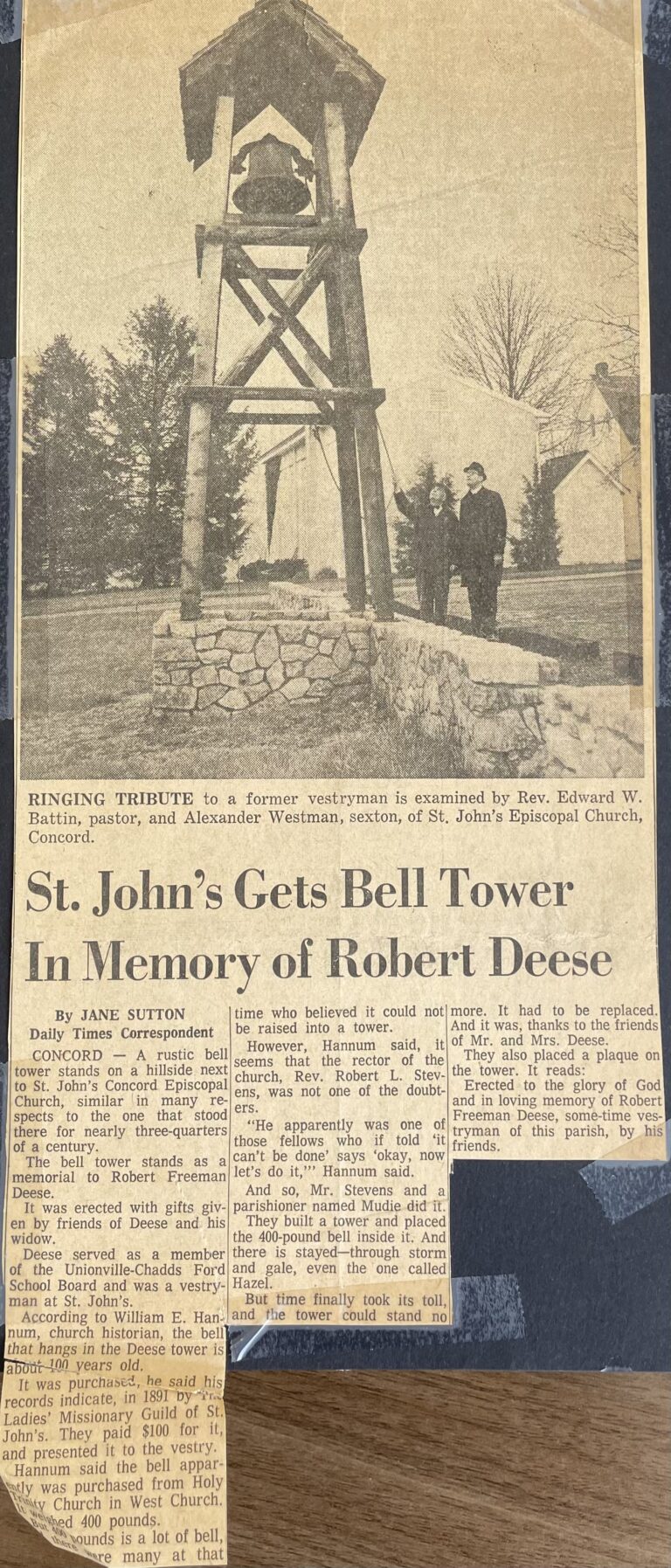

The Bell Tower

The Bell Tower with its bell dates from 1891. The bell was a gift of the Ladies’ Missionary Guild which purchased it in West Chester for $100. It may have been purchased from Trinity Episcopal Church.

Lodging for Clergy

As stated earlier in this history, St. Paul’s, St. Martin’s, and St. John’s Anglican Churches were founded in the same year, 1702. The three churches were served by the same clergyman. St. Paul’s in Chester was the largest of the three churches and probably the home church. St. John’s and St. Martin’s were visited by the clergy from St. Paul’s once or twice each month. This continued to be the case for St. John’s Church for more than a century.

It is ten miles from St. Paul’s in Chester to St. John’s Church in Glen Mills. This was a considerable distance to travel one way on horse-back in those days. To return on horse-back in the same day would have been difficult, especially if the weather were poor. Providing some kind of housing for visiting clergy was necessary. When he visited St. John’s Church, the Rector was probably given lodging with local church families or at the “lodge.” Perhaps the “lodge” was a local inn. The record is unclear.

In 1834 a tenant house was built on church property. A John Hickman was the first tenant. He signed an article agreement with his “X” He was required “to have an apartment in his house to accommodate the Clergy and congregation.” John was in effect the church Sexton. He was the church janitor, cemetery caretaker and grave digger. For this he got housing for free and was paid extra to dig graves. He seems to also have been an usher during worship, showing “Strangers visiting the church a suitable pew for their accommodation.”

It is unclear from the record, but the tenant house may have been called the “lodge.” It stood facing Chester Road (Concord Road) just west of the drive. After standing for almost a century, the lodge was removed in 1931.

The First Rectory

In 1874 an additional acre and thirty-three “perches” of ground was purchased by the church for $400/acre, and the first Rectory was built on this ground in 1875 at a cost of $3,777. This first Rectory was a two-story farmhouse type home, and it stood next to and to the north of the old parish hall. This Rectory was used for housing by the clergy until 1955. Land surrounding the rectory provided a “glebe” for the use of the rector and his family for a garden and to provide pasturage for his animals. From 1951 until it was torn down to expand the new Parish House in 1960s, the old rectory was used as housing for the Sexton and his family. The first floor was used by the Sunday School.

The First Parish House

Plans for the first Parish House were conceived as early as 1931. There was need for more space for church activities. Sunday School classes were meeting in the old Rectory, the dusty church basement, and the back of the church. There was no space for a group of any size to be accommodated except for the church itself.

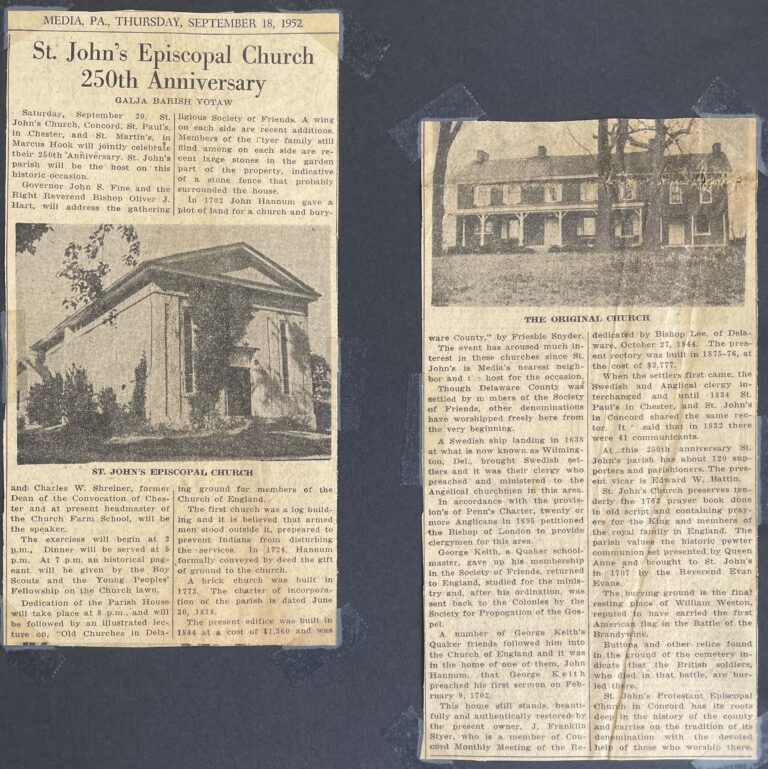

Ground was not broken for the new Parish House until twenty years later on January 30, 1951. The Great Depression of the 1930s and WW II of the 1940s probably hindered such plans. What is now known as the James – McKean Memorial Hall was dedicated twenty-one years later on the 250th Anniversary of the church on September 20, 1952. The builder, James T. Townsend, generously refused to take any personal profit and did the work at cost.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same

The church purchased a horse and buggy in the 1860s for the then Rector, the Rev. Mr. Murphy to use in his ministry. When it became known that Rev. Murphy had resigned, a parishioner wrote the vestry claiming her share in the event the horse and carriage were sold. Perhaps she had contributed towards their original purchase. The vestry decided to gift the equipment to Rev. Murphy instead.

In the 1930s the Rev. Bellis asked a Mr. Willits to serve as the Rectors Warden. The problem was that he had been raised a Quaker and was neither baptized nor confirmed. That was soon rectified in order to comply with Church Canons.

The First Sunday School

The first mention of a Sunday School at St. John’s Church is in the records of 1841. It was established by the Rev. Samuel Stratton and had eight teachers including the Rector and forty-one pupils, twenty boys and twenty-one girls. In the beginning, Sunday Schools primarily gave poor children a basic education. After the establishment of the public school system, Sunday Schools focused on religious education.

An Early Monastic

In 1866 an outstanding worker in the church was first mentioned by the Rev. Murphy. Her name was Miss Sarah Kirk. She eventually became a missionary worker to the poor and oppressed. She went to minister in Philadelphia and established a home in the city for crippled, poor “colored” children. She may have worked with the newly established Episcopal Community Services. Miss Kirk eventually joined an Order of Deaconesses and took monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. She was known to have crossed swords with the bishop of the day.

St. Luke’s, Chadds Ford

St. Luke’s was a small missionary church that had been associated with St. John’s for a number of years. It became independent on Easter Monday in 1885.

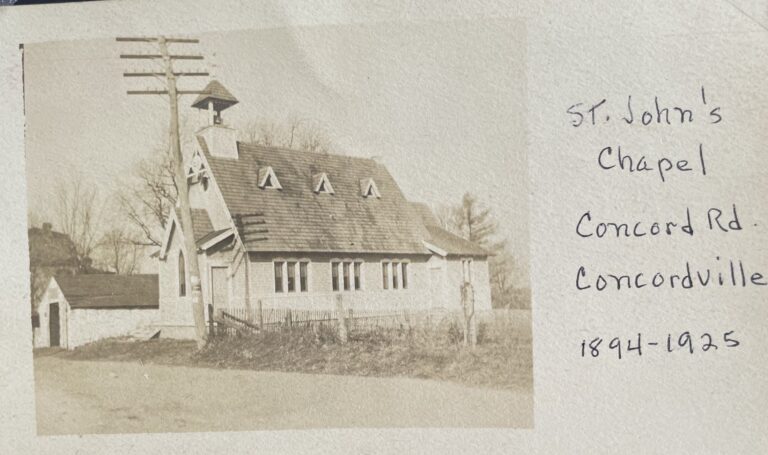

A Chapel in Concordville

In the early 1890s St. John’s established a small chapel in Concordville. It was located along Concord Road near Rt. 1 across from the present firehouse. It is my understanding that the chapel was used when snow and ice blocked Concord Road in winter. The chapel was closed and sold in 1929.

Talk of Closing St. John’s Concord Rebuffed

There was talk in the diocese of closing St. John’s Church. To prove its viability and that they were refusing to close, the parish organized and celebrated its 236th Anniversary on October 2nd & 3rd, 1938. The Rt. Rev. Francis M. Taitt, then Bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania, preached at the celebration of the Holy Eucharist on Sunday, October 2nd. There was a reception and a tour of the church and grounds, and a concert in the afternoon. On Monday night, October 3rd, members of the church, including several descendants of the original church founders, put on a pageant that reenacted the history of the church.

A Scouting Program at St. John’s

Scouting has had a long and strong history at St. John’s Church. Boy Scouts of America Troop 260 was started at St. John’s Church on December 9, 1937. Troop 260 has produced ninety-six Eagle Scouts during its eighty-four years of existence. This is an impressive number. One Cub Scout, one Boy Scout, and three Girl Scout Troops currently meet at St. John’s Church.

Self-Help Groups

Alcoholics Anonymous had its beginnings in the 1930s under the guidance of Bill W. An Episcopal priest, the Rev. Sam Shoemaker, helped Bill develop the 12 Step Program, a recovery program based on the spiritual principles of the Oxford Group.

AA Self-help Groups have been meeting at St. John’s Church for many years. There are currently two AA Groups, a Narcotics Anonymous, and an Alanon Group regularly meeting at St. John’s every week.

A New Rectory

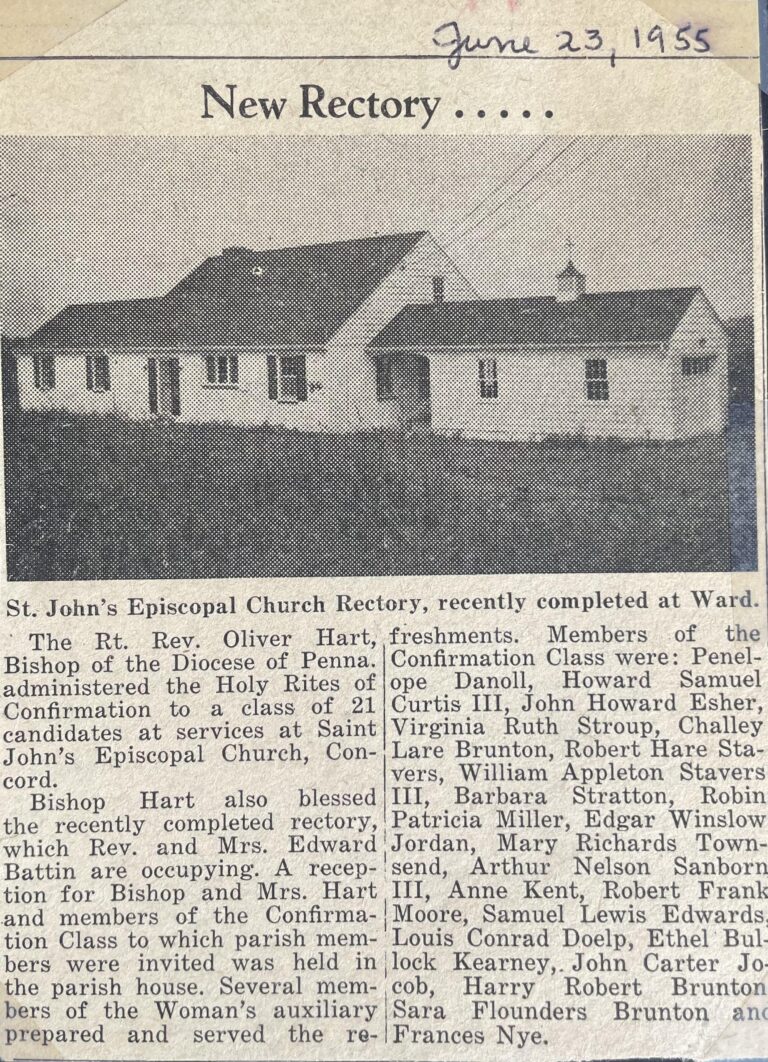

Five additional acres were acquired for the building of the present Rectory which was completed in 1955. It is in the modern bungalow style. Major upgrades will be completed in 2020 in preparation for the calling of a new settled Rector.

A Kindergarten and Nursery School

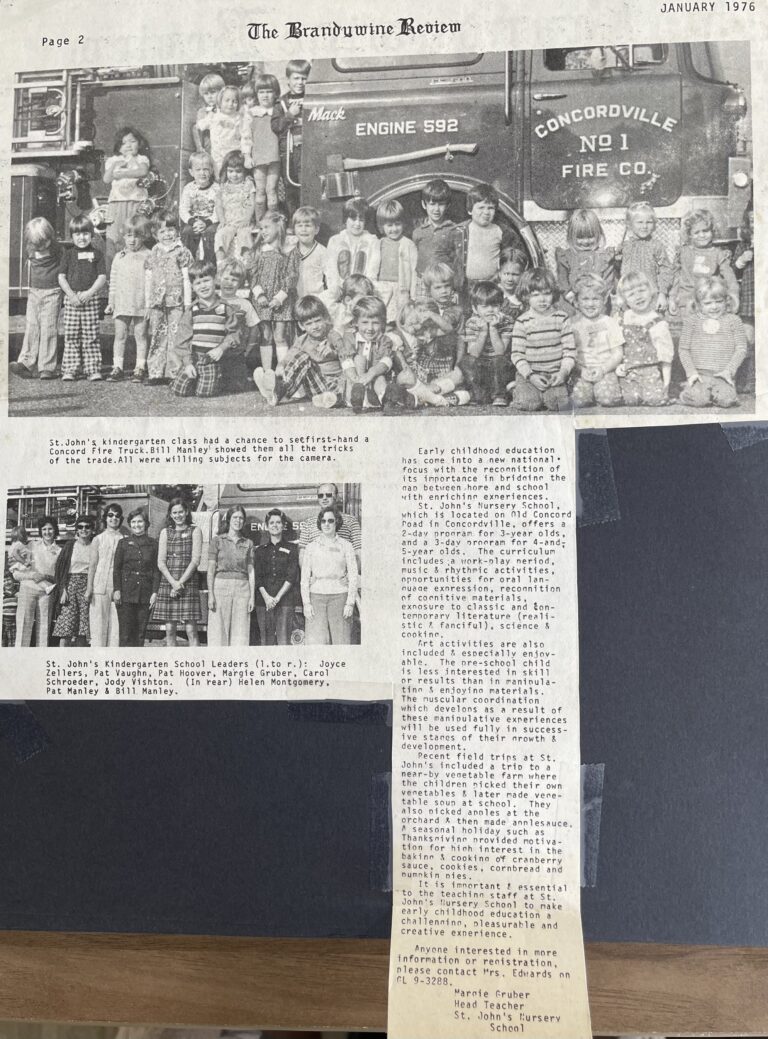

In 1956 in the midst of the Baby Boom, a Kindergarten and Nursery School was opened in St. John’s Parish Hall. It started with one Nursery class and a Kindergarten class and quickly grew to a Three Day and a Two Day Nursery as well as a Kindergarten class. This was a church program with Fr. Battin serving as the school principle. The school would last until it was closed by the Vestry in 2008.

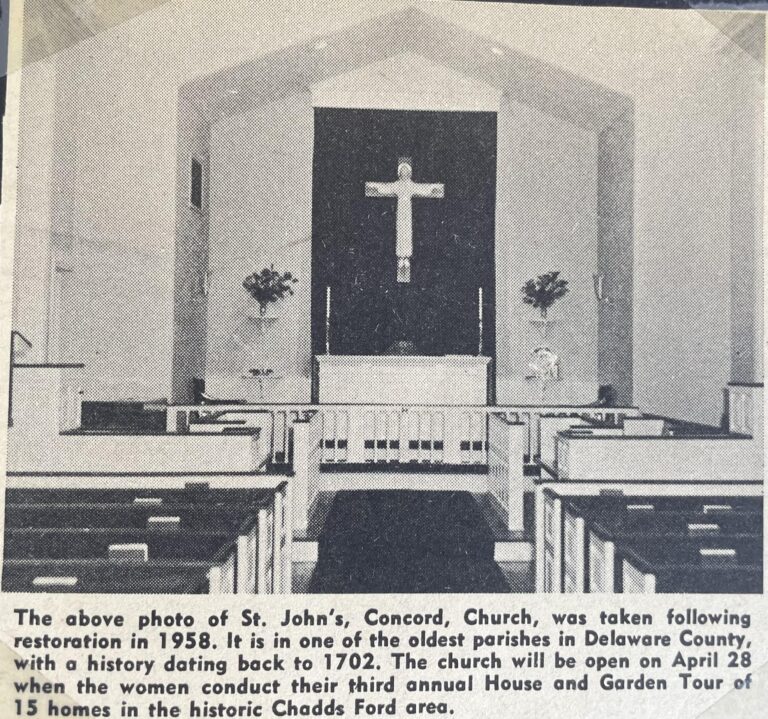

Church Building Restoration and Parish House Expansion

A Capitol Campaign was initiated with a “kick-off” dinner on October 14, 1958. Within two weeks, $56,000.00 was raised. The money was used to expand the parish house and restore and redecorate the church building to its present appearance. The Risen Christ on the Cross mounted on the wall behind the organ console was given at this time. It is assumed that the old rectory was torn down when the Parish House was expanded.

Recent Parish Hall Improvements

During the tenure of Fr. John Sorensen, the parish hall was expanded and upgraded to its present appearance. Additional work is being planned for the near future.

Penn Oak Tree on Church Property

One of the oldest oak trees in Pennsylvania can be found still thriving on St. John’s Church, Concord property. It is known as the Darlington White Oak and is estimated to be about three hundred and thirty years old and more the 15’ in circumference.

Conclusion

Additional historical materials can be found in the parish archive room.

Name

|

Years Served

|

* The Rev. George Keith SPG Founding Priest

|

1702

|

* The Rev. Evan Evans SPG 1st Rector of St. Paul’s, Chester

|

1702 – 1706

|

* The Rev. Henry Nicholas SPG

|

1707 – 1710

|

* The Rev. George Ross SPG

|

1711 – 1712

|

* The Rev. John Humphries SPG

|

1714 – 1726

|

* The Rev. John Backhouse SPG

|

1727 – 1750

|

* The Rev. Thomas Thompson SPG

|

1751 – 1757

|

* The Rev. George Craig SPG SO

|

1758 – 1779

|

* The Rev. John Wade SPG

|

1780 – 1787

|

Bishop William White of Philadelphia Ordained Bishop

|

1787

|

1st American Bishop for the new Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania

|

|

* The Rev. James Conner

|

1788 – 1790

|

* The Rev. James Truner

|

1791 – 1796

|

* The Rev. Levi Heath

|

1797 – ?

|

The Rev. Joshua Reece

|

?

|

The Rev. M. Chandler

|

?

|

The Rev. William Pyree

|

?

|

The Rev. Jacob Douglas

|

1818 – ?

|

The Rev. Samuel C. Brinkle

|

?

|

The Rev. Jacob Douglas

|

?

|

The Rev. George Kirk

|

?

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

The Rev. John B. Clemson

|

1833 – ?

|

The Rev. M.D. Hirst

|

?

|

The Rev. E. Nelson Wiltbank

|

1838

|

The Rev. Alfred Lee (Supply)

|

1839

|

The Rev. Samuel C. Stratton

|

1840 – 1841

|

The Rev. Benj. S. Huntington

|

1842 – 1846

|

The Rev. R.B. Claxon

|

1847

|

The Rev. W. H. Trapnell

|

1848

|

The Rev. Charles Breck

|

1849 – 1852

|

The Rev. John K. Murphy

|

1853 – 1866

|

The Rev. R. Graham

|

1867 – 1868

|

The Rev. John B. Clemson

|

1870 – 1872

|

The Rev. M. Christian

|

1873 – ?

|

The Rev. J.J. Craigh

|

?

|

The Rev. Joshua Cowpland

|

1875 – 1880

|

The Rev. J. Baldwin Dean

|

1881

|

The Rev. Joseph J. Sleeper

|

1882 – 1884

|

The Rev. Fletcher Clark

|

1885 – 1889

|

The Rev. Robert L. Stevens

|

1890 – 1894

|

The Rev. Willis Hazard

|

1895 – 1897

|

The Rev. Joshua Cowpland

|

1898 – 1909

|

The Rev. Thomas Josephs

|

1910 – 1911

|

The Rev. J. Holah

|

1912 – 1913

|

The Rev. Fletcher Clark (Supply)

|

1914 – 1916

|

The Rev. David L. Sanford

|

1917 – 1929

|

The Rev. J. Bagley (Supply)

|

1929 – 1930

|

The Rev. W. O. Bellis

|

1931 – 1943

|

The Rev. Francis C. Steinmetz

|

1944

|

The Rev. John Knewstub

|

1944

|

The Rev. Archibald Judd

|

1945

|

The Rev. J. Marshall Frye

|

1946 – 1948

|

The Rev. E. Clarendon Hyde

|

1949 – 1950

|

The Rev. Edward W. Battin

|

1951 – 1992

|

The Rev. Dean Evans (Interim Rector)

|

1992 – 1994

|

The Rev. Luke Nelson

|

1994 – 2005

|

The Rev. William R. McKean, Jr. (Part-time Assistant)

|

2003 – 2010

|

| |

|

The Rev. Barbara Rivers (Interim Rector) 1st Woman Priest

|

2005

|

The Rev. Dr. John Sorensen

The Rev. Michael Giansiracusa (Assistant Rector)

|

2006 – 2019

2011-2012

|

The Rev. Jill LaRoche Wikel (Part-time Assistant Priest)

|

2012 – 2019

|

The Rev. Daniel W. Hinkle (Interim Rector)

The Rev. Jill LaRoche Wikel (Rector)

|

2019 – 2020

2021 – present

|

Note: From its founding in 1702 until the American Revolution, the Bishops of London had jurisdiction over the churches in the American Colonies.

SPG = Missionary Priests of The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), an early Missionary Society of the Church of England

SO = Slave Owner. Probably several other colonial era priests were also slaver owners.

* = For the first one hundred years, St. John’s, Concord and St. Martin’s, Marcus Hook were served by the Rectors of St. Paul’s Church in Chester, PA.

Swedish Lutheran clergy often served St. John’s Church during the colonial period when there were no English clergy available.

Bold Type = Women Priest

“The Story of St. John’s” compiled 1959 by William E. Hannum, a direct descendant of a founder of the parish.

“Sanctifying Life, Time and Space” by Marion Hatchett